Not many people in Indonesia talk about ianfu. The few that do are independent researchers, as Indonesians are not really concerned about survivors. This is the point that an author and independent researcher, Eka Hindra makes, on the issue of Ianfu in YouTube LetssTalk Feminist on Facebook #7. Eka says that the inspiration came in 1999 when she worked as a journalist at Radio Internews Indonesia. She worked at the Women Program, the first in Indonesia to have a feminist perspective, and not an infotainment women issue, but real journalism who conducted research on the field.

One research she did was Ianfu. Eka then rethought, and searched for a character and remembered. She finished a 250-minute biography of Mardiyem that she recorded and compressed it into 30 minutes. There was a friend, Nugroho, who told her that this issue was so important and nobody covered it, why did she not do it personally. So she met Doctor Koichi, who was a theologian in Salatiga and Semarang. The turning point came in 2002. Mardiyem returned from Pyongyang with Koichi to wrap up the case.

Koichi told Eka, what do you think because Mardiyem was getting old. Koichi returned to Japan in 2003 and the idealistic project was handed over to Eka, with the consideration that Eka was a woman and the content was about sexuality. The second reason was that Koichi returned to Japan and Eka lived in Indonesia. Finally, Eka did it for four years. She went back and forth between Indonesia and Japan. The book Momoye was the result of four-year interviews between myself and Mardiyem which Koichi started and continued by writing this book.

The current edition is a reprint with a revision and terms used. There is also a change in cover. Why Eka reprint Momoye book with a different published? The reason is because the first edition in April 2007 was done by Airlangga Publisher. Then, Eka realised that, at the time of COVID-19 and through chat with friends all over Indonesia, Momoye has become a referral for S1, S2 and S3 students. There are people contacting from the UI to Cenderawasih University asking for access to Momoye which was then very difficult. She later found that the book was too expensive and Eka herself did not have the book. The price was fantastic at Rp. 800,000.

Eka then made some revision for a fair price, which is now at Rp. 140,000. She saw that the paper quality in the first edition was exceptional, and the book had never been illegally reproduced, and it was a pocket edition.

The question is what was the writing process like in those four years? Eka answers that the issue was a financial one because it was an independent research. Koichi had the same experience. Eka met Mardiyem after she finished her work with internews. Why Mardiyem? Because she was the most outspoken survivor and a leader who had the ability to advocate for herself and her friends. Eka was totally focused on her. Then she met other Ianfu and she even went to Southeast Maluku and Northwest Maluku.

She found Lanjo where ianfu was and this was a systematic rap. A number of people gave their supports and this was a form of solidarity. Eka convinced herself that there should not be a time limit to do this. She met 50-60 ianfus in 20 years, with interviews ranging from 4 days to nine years. “I was not like a journalist who used coercion, but I came as a friend. The challenge was their health,” says Eka.

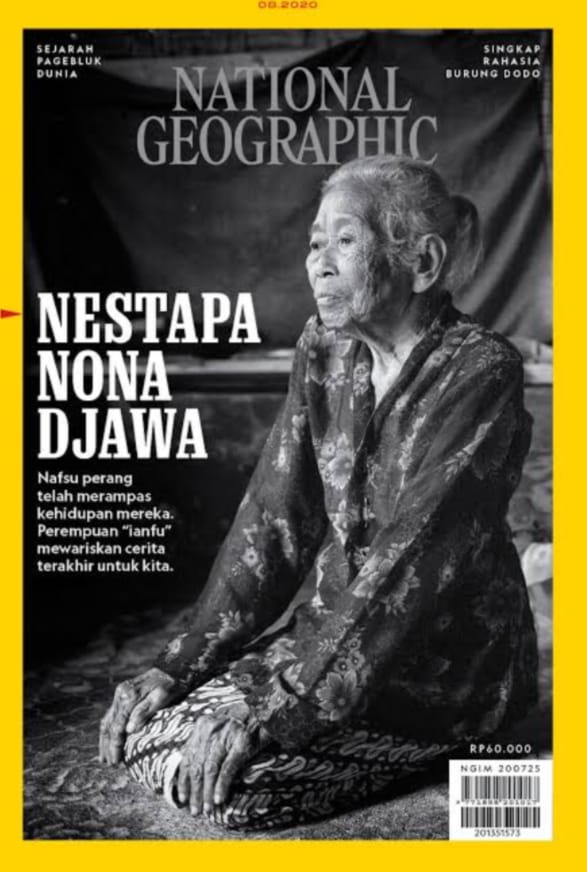

Sri Sukanti was one of the Ianfus, and she was the youngest in the world. She was raped at 9 years old. NatGeo wrote about it in 2020. It was not a personal previlegde but in the end, the ianfu issue could be hear worldwide. NatGeo also wrote about its human aspect. Eka was involved in that process for 2.5 years and it was very interesting. The research and coverage, along with a photographer named Azhar who was in one team with Eka, was as she intended for a re-generation.

Her research method was field investigation, starting when she was 20 years old. She started by making a journal for herself, and she noted a lot. For Eka when Momoya was coming, it was a first step which would lead to other books, and that would be her inheritance to the next generation.

She focused on the writing, based on the interviews she conducted on the field. There was no national archive nor any document about Iansu at the National Library. She got her supporting data from international sources, where she had string network, and obviously there was copyright. They asked for the data she had and she gave them for advocacy.

The Indonesian Government remains Uninterested in Addressing the Issue with the Japanese Government, Unlike South Korea.

The book “Momeye Call me” was based on oral history. Eka wrote 100% based on witness accounts. Koichi added an epilogue. The Book Momoye starts with a young girl, growing into a teenager and trapped in a promise, and Mardiyem is the main and genuine character who has a strong, detailed memory. She experienced the first rape and what happened then in the camp - in Room 11, with the first group on Jawa Island and then the subsequent groups.

What happens next after the war: She got to know her husband, an ex-Romusha. There was not-too-high frequency sexual trauma. She returned home and experienced social discrimination. She had a catering business, but it collapsed because no one ordered from her because of their reluctance of her past experience as a Japanese sex slave. She met a friend from Telawang and went to LBH (Legal Aid) Jogja and met with Tuminah. Mardiyem opened up since 1993, while Tuminah opened up in 1992. Then there was Sri Sukanti. After the war, many survivors died of diseases –that had to do either with their reproductive organs or cancer.

The Book Momoye has 300 pages.Eka became friends with them after four-years of interviews. One chapter was about Mardiyem who told her story when she was in Balikpapan. Eka treated her as equal. She faced many challenges, for example when she was ready for an interview but the survivor was asleep, as what happened in the case of Suharti when she was with her for ten days. Eka had so much respect for Mardiyem, with the latter completely mad in the end. Eka stayed with them for 10 days. She noticed that it was truly hard to be survivors. “So Mardiyem was angry. She said I was a fool not speaking Javanese. This was a reminder. No more war because as Mardiyem said, where there were bullets there would be women, they were one package with rapes in war. There was a terrible conflict that night,” says Eka

Momoye launched in April 2008 during Kick Andy program. Mardiyem came. She already delivered the book and made commitment with Koichi. Six months after that, Mardiyem died of old age. Everything was documented.

Why "Ianfu"?

Why “Ianfu”? The use of apostrophe shows that it is related. For the Indonensian and Dutch context, there was no Jugun Ianfu like in China. Eka knows because she met with the survivors, Thailand and China, these women were brought to the war fronts. When the Japanese soldiers went to war, they raped these women at the same time. There was no such case in Indonesia. What happened was that the Japanese soldiers returned to bases after the war, where prostitution houses were made available- those were the Ianfus.

So in general, the Pacific war did not happen in Indonesia. It was outside of the war theatre. And people had little conflict. The Japanese had to be nice to the people of Dutch Indies because they needed their support. Then there was a Slogan 3 A. They came with tricks that there was no war. This was the relations with "Ianfu" or sexual slavery. There was no proper term in Japan hence the euphemism with apostrophe, because they survivors did not want to be called the entertainers.

And what about the trauma? Eka Hindra says that the State should have taken care of it because the State had the mechanism, the political power, and the money to design healing program. In Taiwan, there was a book about how an organisation brought Ianfu dreams into reality "Ahma" or grandmother(s) but specifically referred to Ianfu. How this organisation helped childhood dreams. So some became stewardesses. Some worked in offices and had up-to-date photos. Or others with dreams of getting married wearing beautiful wedding dress. The organisation made their childhood dream come true by taking their photos as a form of healing program, and that organisation was government organisation.

Meanwhile Eka witnessed a long trauma healing one day, for example, when she was asked by a Japanese friend to ask Sri Sukanti, the youngest suvivor, to come to Japan. Sri Sukanti has severe trauma, and she had a meagre existence, economically. Eka was confronted with many difficulties – i.e. internal issue with the husband who was much older.

Sri Sukanti went to Japan in the end. Eka saw the trauma destroyed her mentally. Sri Sukanti experienced time disorientation. She thought she was in Solo, when in fact she was on the way from Salatiga, to Solo, Jakarta, and Japan. The most extreme demand was that she asked to be returned home, otherwise she would jump from the 8th floor. Eka was there to help. Then something extraordinary happened. She found Gudang Garam cigarette in Japan and gave it to the survivor. We had a roadshow in other city - Fukuoka.

When Eka met with the survivor and the family, she emphasised that she was not a sex slave in Japan. She then handed the Book Momoye to the family without any thought about profit. She thought it could be used as a tool for advocacy. They supported the ianfu issue.

Eka also told a story when she went to Blitar, she had to go through jungles. She was asked to leave as soon as she arrived. She came back two years later. The survivor had no education background, was illiterate, and had different knowledge level than Mardiyem. They did not know, so Eka explained the history behind her writing the book Ianfu.

The text in a 2003 advertisement at Merdeka Newspaper said, “Looking for Ianfu, we will give you money”. That is what people then understood. What did it really mean? “In the past they were not paid, and now they were paid, did that mean that they were sex workers. Not as human righhts. This is what we need to address to this day,” says Eka. She iterates that war destroyed humans, and that is what happened to Ianfu, Heiho and Romusha. (Ast)