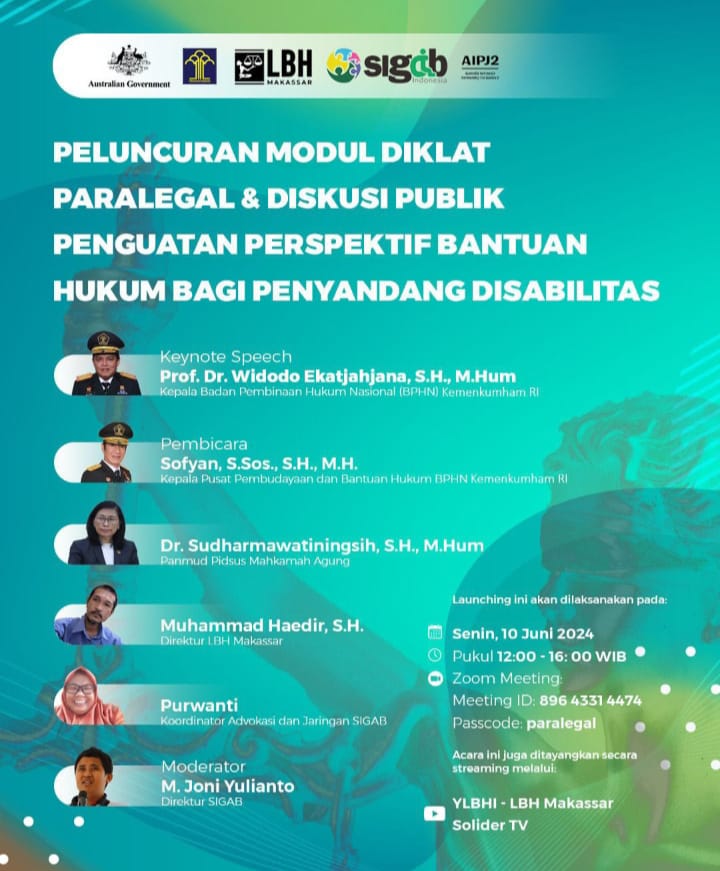

It starts with a COVID-19 pandemics transition momentum, where the existence of legal aid organisations becomes stronger through the works of its lawyers and paralegals. How to strengthen and protect the paralegals. How to differenciate between paralegals and lawyers.

Then comes the Minister of Law and Human Rights Regulation No. 3 Year 2021, and the training that follows to get the competence. Then comes the modules that articulate the boundaries. Each presenter talks about the key points of each material being presented to the paralegals. Why the key points? Because there are ‘unexpected’ things there. There are materials on reporting and documentation techniques. Presenter talks about how to make activity documentation when it should have been about complaint reporting and legal documentation. In essence, it is about the proposal, the binding, the thickness, the content and the photos, rather than about the substance or key points when making a report, how to submit complaints to the police. It is about how to make photocopy of documents, not about how many in 24 hours. It is about whether the biding is using spirals or tapes, when what they need to know is the substance. These facts lead to the necessities for paralegal training modules. This is what Masan Nurpian from National Law Development Agency during a public discussion organised by SIGAB Indonesia in collaboration with Makassar Legal Aid.

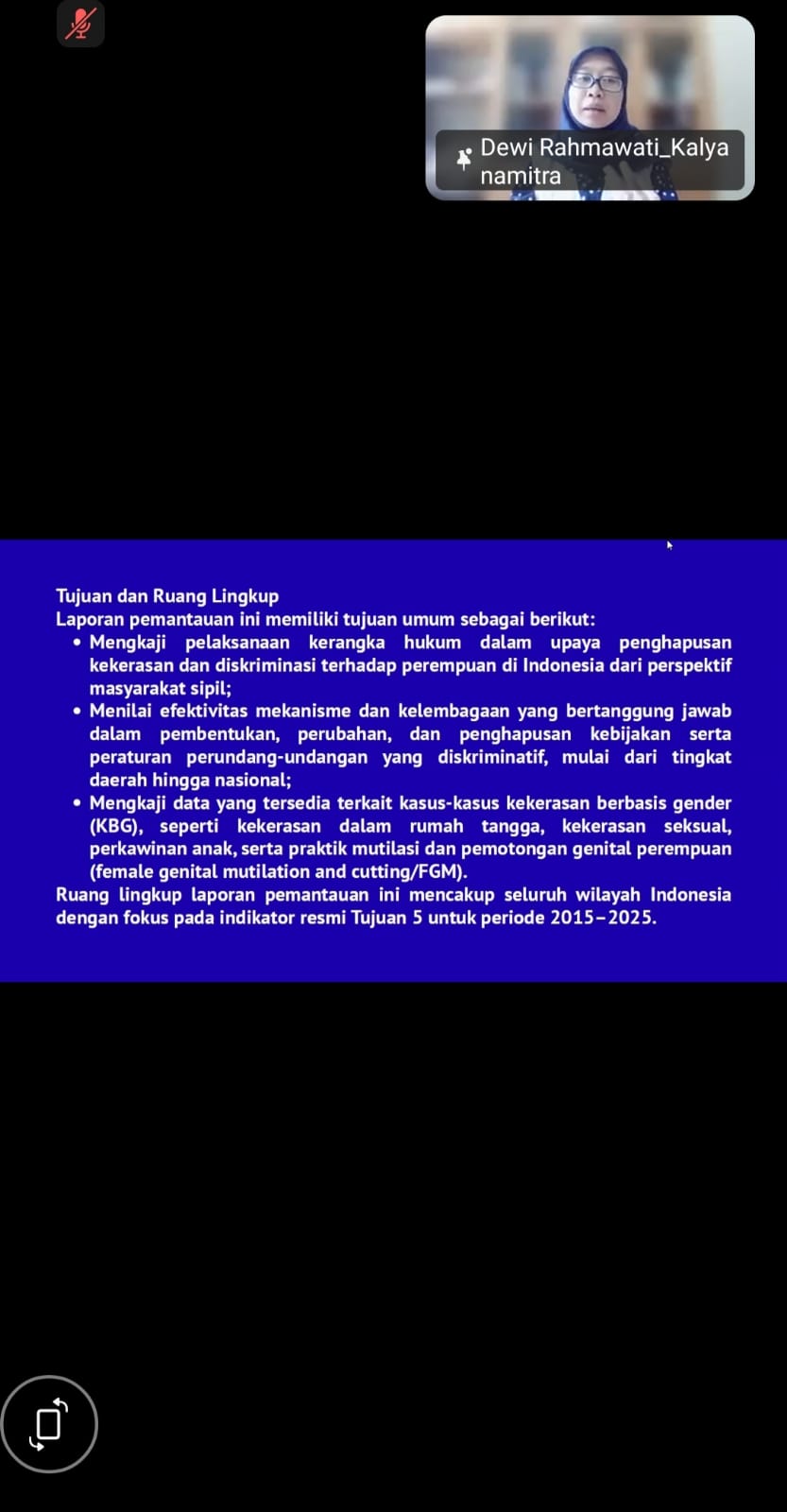

Masan emphasises that there is much emphasis today on inclusive legal system, which necessitates paralegals from certain communities. There are three categories, if we look at it from a legal aid perspective. The law refers to senior citizens, pregnant women, children and disability. But human reference for its part points to refugees, migran workers, indigenous communities, children and women. There are internal debates regarding women, whether the State can cover all and how the State prioritises any of them. Then how can the State cover all in its budgeting without making any discrimination? “Obviously the State would not be able to do that.” Says Masan

But how will the State makes its considerations with regards to non-discrimination. If women are deemed as a vulnerable group, then what kind of women are we talking about? How can legal as, as a policy, provide inclusive legal aid for people with disability and otrher vulnerable groups.

“We are drafting a change in legal aid law or legal aid draft law. The academic text is completed at the end of 2023. We are now busy thinking about political transition in 2024. Once the political transition is over, we can start to work intensively on the draft.” Says Masan.

The draft is still being reviewed before the draft becomes a standard legal aid. A consortium of YLBHI, LBH APIK, and other legal aid organisations are developing an operational standard for legal aid service as a requirement, regardless of branch offices.

The emphasis in litigation is the perpetrator. Victims may access litigation services. Paralegal should understand the Minister Regulation No. 4 Year 2021 on Standard Legal Aid Services. This is integrated into the National Action Plan for Human Rights and National Action Plan for Disability. The application would indicate which recipients of legal aid are people with disability or non-disability. The National Law Development Agency (BPHN) provides assistance to SIGAB so that the letter can get accredited as a legal aid organisation for 2025 to 2029.

The draft legal aid re. changes in law only highlights the crucial aspects. How to provide free legal aid to recipients – by encouraging recipients to provide legal services for other legal services. There are needs that accommodate inclusively the needs of legal aid recipients, because the state does not provide direct legal aid, or aid to legal aid organisation It works with lawyer oreganisations to help legal aid recipients. The recipients of legal aid are vulnerable communities. Non-litigation legal aid is the primary legal aid. What is a primary legal aid? Primary legal aid means that cases must be addressed through litigation. “We are slowly working on directing the cases to litigation, through the budget politics. Why? Litigation is simpler. Non-litigation is more complex because it involves state’s responsibility. It involves larger budget than litigation. We are gradually working on changes to standard costs, in collaboration with LBH, YLBH and IJRS. How does non-litigation become the first step in dealing with a case, whether criminal or civil, or state administrative,” says Masan.

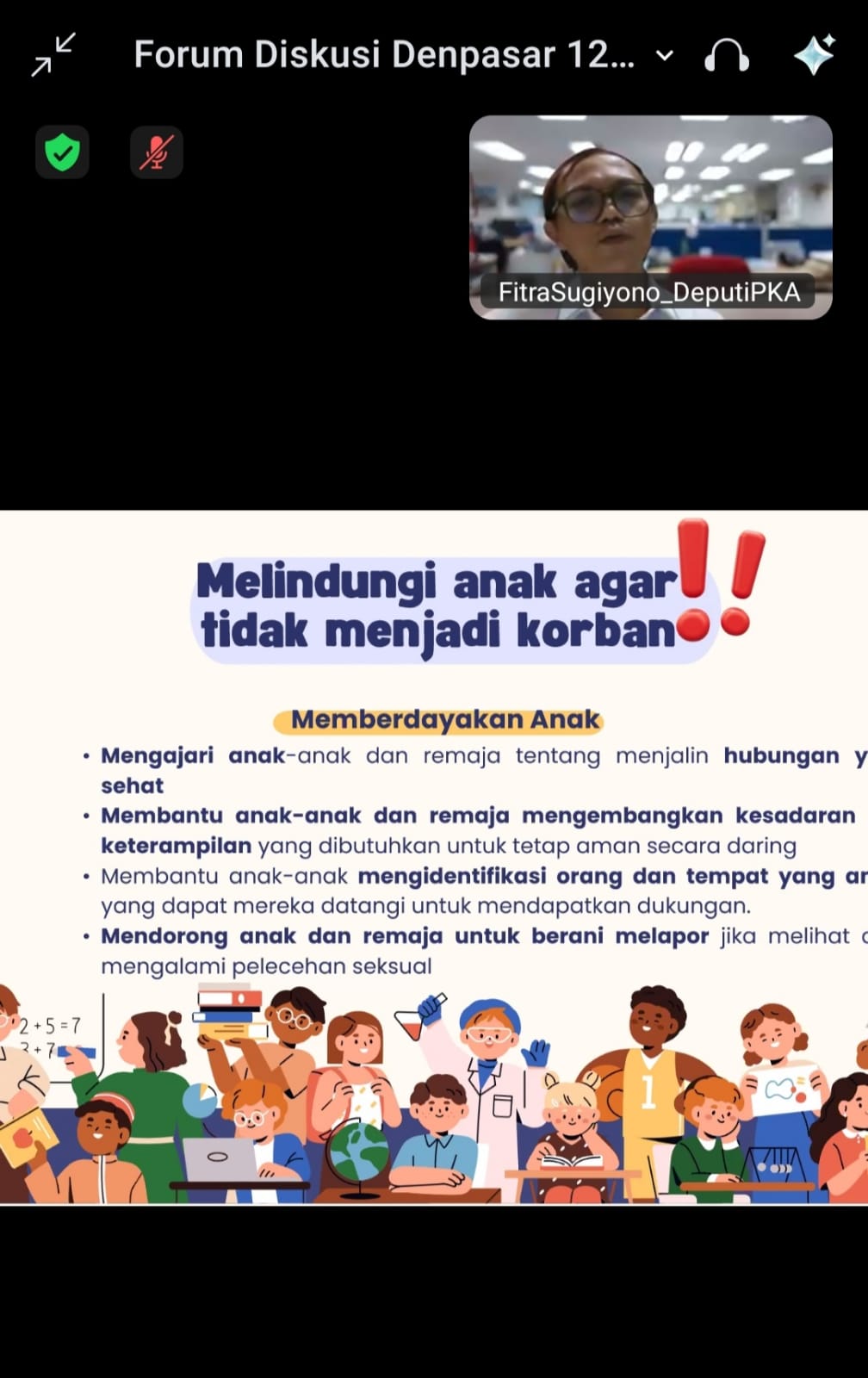

However, there are regulation issued by the Indonesian Police, the public prosecutor office, and the supremen court regarding diversion and restorative justice. The following shows when legal aid plays a primary non-litigation role. The key question is who plays a central role? The answer is a paralegal, who plays important role in non-litigation outside of the court. This does not demean the roles of the lawyers. Lawyers are important on their own.

A paralegal is critical for non-litigation outside of the court. The next policy would be standard for legal aid services: Starla Bankum. It involves assessment of vulnerability, which necessitates the participation of legal aid recipients. This assessment should not be assigned to the administrator. Instead, it should be done by the provider of legal aid services: a lawyer or a paralegal in legal aid organisation. Perhaps, the recipients of legal aid are able to conduct a self-assessment. Jangan misalnya orang mampu tetapi menganggap dirinya tidak mampu. Self-asesmen is essential, but an assessment by a legal aid provider is equally critical. (Ast)